PM Modi likens MVA to vehicle with no wheels or brakes

PM Narendra Modi kicked off the BJP election campaign in Maharashtra with an all-out assault on the Congress-backed Opposition Maha Vikas Aghadi alliance.

While it is important to make the best of potential of energy sources, it is equally necessary to recognise their limitations and open ones mind to alternatives

Should the nuclear sector have a greater role in India’s energy plan? The question is one that is controversial in many circles. R B Grover, Emeritus professor, Homi Bhabha National Institute and member, Atomic Energy Commission, while speaking before the Indo French Technical Association, at Mumbai, outlined the many issues that arise before the energy planner, to help see the nuclear option in context. The context was the proposed nuclear project at Jaitapur, on the Maharshtra coast, said to be, at 9,900 MW, the largest in the world.

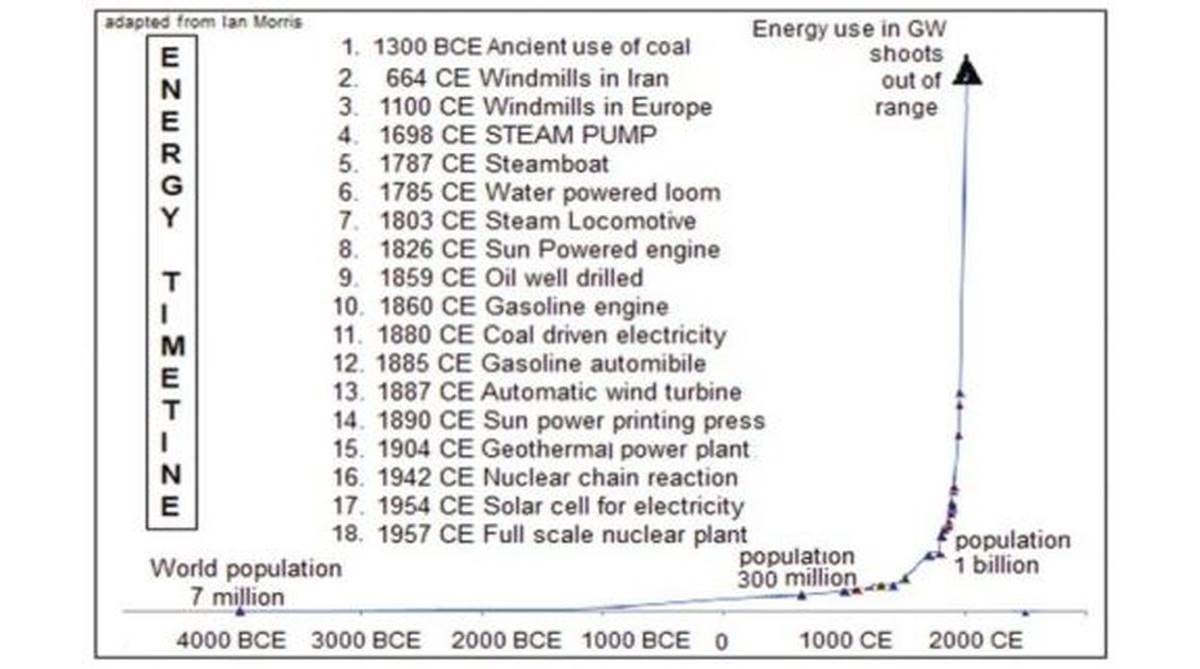

Grover commenced his presentation with a description of how energy has shaped the growth of civilisation.

While there were great developments in science and the arts over the centuries, it was only in the 18th century that mankind was empowered with plentiful energy. Till then, water, wind and coal had been used, and industry had grown, but coal, the great driver, could not be mined in quantity. This was because mines rapidly got flooded and limitations of technology in pumping out the water limited the depth to which the mine could go. In England and Europe, where industry started expanding, recourse was taken to burning wood, with limited benefit and at the cost of forests.

Advertisement

In 1698, Grover said, the steam driven, mine dewatering pump was developed, and this brought about a revolution in the output of coal. The vast supply of coal that steam made available, in turn, supported steam power, to drive machinery, manufacturing, spinning and smelting, the steam locomotive, and the steamship, which could sail, at will, the world over.

However, the early steam engines were notoriously inefficient, at just one per cent, growing to three per cent, at the start. And when engines got more efficient, the scales grew high, leaving us with the crisis of global warming that the countries of the world face today.

In the rising prosperity of earlier times, there was the increase in the number of horse drawn carriages in cities, and the streets, Grover said, were covered with horse dung. So severe had the problem become, that it was said that many large cities would soon disappear! And then, the freely available coal was now used for domestic heating and the cities were enveloped in a pall of soot. The London smog is legendary – one could not see one’s own hand if one stretched one’s arm, it was said. And the animal waste and soot in the air brought infection and respiratory disease. The entry of the IC engine, the automobile and electricity companies put an end to all these troubles, but they brought with them the dependence of the world on huge energy, and the present global challenge to keep up the supply without further damage to the environment.

Coming to India’s own needs of energy, Grover noted that during the last decade, electricity generation has grown by nearly six per cent every year. The problems of distribution, however, have not made it possible to provide assured service and there is increasing reliance on private generation.

An estimate of how much power India needs could be arrived at from statistical bases, but it may be more instructive to consider how much power we need to provide Indians with a reasonable level of well-being. There exists a correlation with development indicators of a country, the dimensions of health, education and GDP, and the power consumed per capita.

Countries that score high on development are found to consume more than 10,000 units of power, per capita. India produced 1,500 billion units of electricity during the 2017-18. For a population of 135 crore, this works out to 1,100 units per capita. According to the International Energy Agency, the world average per capita electricity consumption in 2015 was 3,052 units and in India’s comparable neighbours, the figures are: Malaysia – 4656 and Thailand – 2621. Grover hence considered 5,000 units, per capita, to be a reasonable target for India to place before herself. Taking it that the population would plateau at 1.6 billion and the transmission losses of electricity are contained at seven per cent, this implies production of 8.600 billion units, Grover said.

Globally, the share of coal and oil in power production is 81.4 per cent, of nuclear, it is 4.9 per cent, of hydro, it is 2.5 per cent, of biofuels and waste, it is 9.7 per cent and of wind, solar and others, it is just 1.5 per cent. India’s own hydro production in 2017-18 was 122 billion units and the potential from wind and solar is 1,840 billion units. All renewable sources, hence cannot meet even a fourth of what we need. While we recognise, with the world, the need to cut down our reliance on coal, Grover said changing the mix and reducing the role of large investments made so far would need careful study.

In respect of the emphasis being laid on increasing production from wind and solar, Grover drew attention to two indices of a utility that need to be measured — the net energy gain, or energy return rate, and the system cost. As it takes investment of energy for utilities to be set up, it is important to measure the ratio of the energy output by the utility to the energy used in setting it up. Grover referred to a study in 2006 by the Princeton University, which found that this ratio, the Energy Returned on Investment, was high in the case of coal (38 per cent), nuclear (62 per cent), large hydro (57 per cent) and wind (39 per cent) but low in the case of solar PV (six per cent).

In addition to the cost of the investment and operation of a utility, the system cost is what the distribution network and other utilities have to bear because of features of the first utility. In the case of wind and solar, the output is intermittent, or only when the wind blows or only when it is sunny. The distribution mechanism, the grid, hence needs to make provision to keep up the supply when these sources are not available. In the case of wind and solar, States provide various subsidies, as these sources are “green”.

In many cases, at the times when the wind or solar plants are peaking, thermal plants in the grid are turned down. This amounts to further subsidy, this time at the cost of the thermal units.

While there are limited places where hydro plants are possible, there is a limit to the number of wind farms that can be installed in a region before efficiency falls. Solar farms too, would consume land resources. While it is important to make the best of the potential of these sources of power, it is important to recognise their limitations and open one’s mind to alternatives.

(S Ananthanarayanan can be contacted at response@simplescience.in)

Advertisement